Epigenetics: How Your Environment Affects Your Genes

I’d like to talk about epigenetics today, which is how your environment talks to your genes. Our cells are capable of reading the state of our environment and activating or deactivating genes. This means that, based on the choices we make, we can turn on genes for health or turn off those health-promoting genes. In other words, it is your health behaviors such as diet and activities, that determine whether the health-promoting or the health-robbing genes are active.

picture source: scienceinschool.org

The vast majority of diseases I see in primary care clinics, including high blood pressure, diabetes, obesity, mood problems, autoimmune problems, osteoarthritis and memory problems, are a result of how your genes are interacting with your environment. Eating foods that are high in carbohydrates, such as flour, potatoes, and high fructose corn syrup, will turn on genes that promote weight gain and inflammation. Eating greens, sulfur-rich and brightly colored vegetables, and grass-fed meat and avoiding starches turns on genes that lower inflammation and lead to a trimmer waistline.

Important Factors Influencing Epigenetics

picture source: truthaboutabs.com

Another important factor influencing the epigenetics of your cells is exercise. Our bodies expect us to be physically active and to occasionally need to run from predators who would like to have us for lunch. When we maintain daily activity, walking 10,000 steps a day for example, genes that lower inflammation and lead to a slimmer waistline are activated. On the other hand, if you are not active, genes that worsen inflammation will activate and lay fat down around your intestines. That fat in turn, churns out more inflammation. The best defense is to slowly increase your activity. A pedometer that counts your steps is a great way to start.

The three components of exercise are aerobic activity, stretching, and strength training. For most adults and especially those with MS, the muscles are often stiff and shortened. For that reason, a regular program of stretching every day will be very beneficial. Yoga, tai chi, and pilates offer excellent stretching routines. Alternatively, consult with a physical therapist or athletic trainer to help get your stretching program going. Resistance training builds muscle strength and also helps prevent loss of muscle. Again, working with a physical therapist or athletic trainer can help you design a strength training program specific to your needs.

By Dr. Terry Wahls

Intensive Nutrition to Overcome Multiple Sclerosis

Dr. Terry Wahls is a professor of medicine at the University of Iowa and has been battling Multiple Sclerosis since the winter of 2000. After her symptoms progressed to near complete debilitation, Dr. Wahls began restudying the available medical literature on the disease with immense intensity. Her findings have led her to a miraculous recovery within less than a year. This is her remarkable story:

By Dr. Terry Wahls

About Dr. Terry Wahls

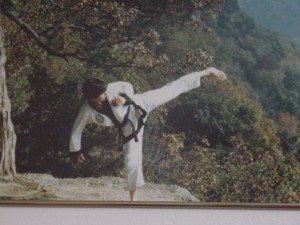

In choosing a starting point for this memoir of illness and recovery, it seemed only natural to go back to the time when I felt strongest and most alive in my body—competing as a black belt in Tae Kwon Do when I was in college. At 6 feet tall, I had always been powerful, but Tae Kwon Do gave me a grace and agility I had never had.  I broke boards with punches and flying sidekicks and competed in full-contact sparring. My signature maneuver was the tornado kick. As the referee commenced the round by pulling back his arm, I’d leap through the air in a spinning spiral and with my long legs I’d often catch my opponent off guard and drill her to the mat. In 1978, I earned a bronze medal in the Women’s Welterweight Division in full contact free-sparring.

I broke boards with punches and flying sidekicks and competed in full-contact sparring. My signature maneuver was the tornado kick. As the referee commenced the round by pulling back his arm, I’d leap through the air in a spinning spiral and with my long legs I’d often catch my opponent off guard and drill her to the mat. In 1978, I earned a bronze medal in the Women’s Welterweight Division in full contact free-sparring.

Part ballet, part combat, sparring was a brutal sport, but I loved the adrenaline surge it gave me. I competed nationally, and in 1978 I won a bronze medal in free sparring at the trials for the Pan American Games in Washington, D.C.

The following fall I began medical school. Although I continued to train and teach Tae Kwon Do, I stopped competing in full contact sparring, not wanting to risk anymore punches or kicks to my head. Never again would I have such quick reflexes and powerful kicks, or the unshakeable belief in myself as invincible and capable of anything. I switched to less demanding sports like biking and rock climbing.